| A worthy tribute to Puccini by Sarah Noble | |

| Puccini: Madama Butterfly Opera Australia Sydney Opera House 30 December 2008 | |

| This revival sees the return of the singer for whom the production was created. Cheryl Barker is an internationally fêted Cio-Cio San who could possibly be forgiven for resting on her laurels. Instead, she brings her experience to bear in an interpretation which seems freshly created. She is an irresistible Cio-Cio San: not a relentlessly solemn and pathetic figure, but rather a spirited, passionate heroine whose laughter is as infectious as her tears are moving. Her voice may no longer have the girlish brilliance of ten years ago, but her vibrant tone is as thrilling as ever, and her darker timbre brings with it a host of new possibilities. Barker handles Butterfly's incredibly demanding music with typical panache and attention to detail. Her rendition of the famous "Un bel di" is especially impressive, transcending the aria's warhorse status to bring out its every detail and reinstate its very real emotion. Opera has few villains so universally reviled as Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton, the feckless American sailor whose abandonment of Cio-Cio San leaves her no option but suicide. That, at least, is the theory, but many tenors have found a way to give Pinkerton at least a hint of humanity. Julian Gavin's Pinkerton is more gormless than ruthless: a gauche tourist, deeply infatuated with his bride but fundamentally incapable of understanding the implications of his actions. Gavin's singing is refreshingly refined: he delivers a lyrical and dynamically varied performance, full of colour and happily free from bellowing. | |

|

Barry Ryan brings gravity and expansive tone to the role of Sharpless, responding astutely in his crucial encounter with Cio-Cio San despite occasionally awkward Italian diction. Graeme Macfarlane is curiously appealing as the incorrigible marriage broker Goro, flitting about the stage and lacing his singing with just the right dash of mischief. Jud Arthur makes a striking cameo as the demonic Bonze, putting his remarkable bass voice to wonderfully scary use. Luke Gabbedy's appearance as the preening Yamadori is a little on the quiet side vocally, but he cuts a fine figure: maybe Butterfly should have accepted him. Young Artist Andrew Moran is strong as the Imperial Commissioner, while Jane Parkin, recently seen singing Cio-Cio San for OzOpera, is excellent as Kate Pinkerton. Maestro Shao-Chia Lü leads the orchestra in a performance of astonishing richness, beautifully shaped and carefully considered. There's stellar playing throughout, particularly from the strings. Some slight wrangling over tempo in the early moments of the opera was quickly resolved, and Lü's reading was as magical as the production, allowing the orchestral playing to rise as far as possible above its unhelpful pit conditions while supporting his soloists with care. The chorus is splendid, the women's voices blending gorgeously in Butterfly's entrance (surely one of the loveliest moments in all opera) and in the famous Humming Chorus. Reviving such a perennial favourite may seem a rather safe way of launching a season. But this particular Butterfly, with its strong cast, excellent conductor and eternally exquisite production, is no dull, everyday choice. Coming as it does on the heels of a season in which the company suffered a barrage of criticism and the sudden, tragic death of its music director, Richard Hickox, this revival of Madama Butterfly is a welcome reminder of all that's good and admirable about the company; and, a week after his 150th birthday, it's a worthy tribute to the genius of Puccini. | |

| Text © Sarah Noble Photos © Branco Gaica |

Billy Budd by Benjamin Britten. Opera Australia. Conductor: Richard Hickox. Director: Neil Armfield. Sydney Opera House, September24. Tickets: $99-$240. Bookings: (02) 9318 8200. Until October 16.

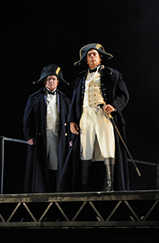

TEN years after its premiere, director Neil Armfield's production of Benjamin Britten's opera Billy Budd remains fresh and compelling. Dominated by a movable rectangular platform that rises, falls and circles an otherwise sparse stage, its great virtue is that nothing is allowed to distract from the moral drama that unfolds.

At this production's core are three magnificent performances. Although Peter Coleman-Wright's singing in the original production had greater richness of tone and complexity of colour, fellow baritone Teddy Tahu Rhodes is still a fine Billy Budd. Singing with a clear, focused tone and impressive agility, his firm, youthful-sounding voice is well suited to his character's exuberant good nature. Rhodes's characterisation is a winning mix of virile magnetism, artless simplicity and, ultimately, moral strength. And, yes, his shirt does come off for a while during the first act.

Tenor Philip Langridge's Aschenbach in Opera Australia's 2005 production of Britten's Death in Venice was extraordinary. Here, as Captain Vere, he is almost as good. Despite showing occasional signs of strain in his top register, Langridge's sinuous line, superb diction and sensitive phrasing illuminate Vere's inner torment at the excruciating moral dilemma he faces. He wants to save Billy from the gallows but his sense of duty cannot allow it. The pain and grief at what he is forced to do are seared into Langridge's vocal timbre.

As the black-hearted Claggart, bass-baritone John Wegner almost steals the show. It is a commanding performance of imposing malevolence and slow-burning intensity. He sings with stamina and strength, investing his voice with a burnished dark-hued tone. Wegner also captures his character's seething heart of darkness. Homoerotism is acknowledged without being overdone and twisted self-loathing adds complexity to a convincing portrait of evil.

The three leads receive able support from the rest of the all-male cast. The male chorus also has a prominent role in this opera. Sustaining good balance and blend throughout, they're equally impressive in hushed, sotto voce passages and full-voiced, fortissimo outbursts.

Apart from the occasional blemish, the orchestra responds to Richard Hickox's inspired direction with polish and refinement.

OA has been criticised recently for its musical standards and production qualities. There can be no more eloquent rebuttal than this outstanding production.

Two days before the end of 2008, Opera Australia opened its 2009 season with perhaps the most popular opera of all, Puccini's Madama Butterfly. Moffatt Oxenbould's production, now twelve years old, remains as enchantingly youthful as Cio-Cio San herself. Cluttered exoticism gives way to an approach revelatory in its simplicity, where naturalism mingles seamlessly with stylised, balletic movement and elements of mysticism. The design by Russell Cohen and Peter England evokes a fragrant and sensual Japan, the spare, formalist set contrasting with the startling blues, pinks and reds of those who populate it. Robert Bryan's lighting design creates some extraordinary effects; the glow which surrounds Cio-Cio San in her midnight vigil is especially striking. It is a production which is suggestive rather than slavish in its detail, drawing inspiration from Oriental tradition without applying a theatrical concept so rigorously as to overshadow the opera's human centre - or its music.

Two days before the end of 2008, Opera Australia opened its 2009 season with perhaps the most popular opera of all, Puccini's Madama Butterfly. Moffatt Oxenbould's production, now twelve years old, remains as enchantingly youthful as Cio-Cio San herself. Cluttered exoticism gives way to an approach revelatory in its simplicity, where naturalism mingles seamlessly with stylised, balletic movement and elements of mysticism. The design by Russell Cohen and Peter England evokes a fragrant and sensual Japan, the spare, formalist set contrasting with the startling blues, pinks and reds of those who populate it. Robert Bryan's lighting design creates some extraordinary effects; the glow which surrounds Cio-Cio San in her midnight vigil is especially striking. It is a production which is suggestive rather than slavish in its detail, drawing inspiration from Oriental tradition without applying a theatrical concept so rigorously as to overshadow the opera's human centre - or its music.  Catherine Carby's presence as Suzuki seems like luxury casting, but in fact she's precisely as luxurious as the role itself demands. Suzuki is commonly cited as the archetypal Thankless Mezzo Role, but while she mightn't have a great deal to sing, her presence is nevertheless vital. Carby fills this role with delicate sincerity, and when she does sing, her shimmering mezzo is a delight, lighter than might be expected in the role, but surprisingly powerful.

Catherine Carby's presence as Suzuki seems like luxury casting, but in fact she's precisely as luxurious as the role itself demands. Suzuki is commonly cited as the archetypal Thankless Mezzo Role, but while she mightn't have a great deal to sing, her presence is nevertheless vital. Carby fills this role with delicate sincerity, and when she does sing, her shimmering mezzo is a delight, lighter than might be expected in the role, but surprisingly powerful.  Shakespeare’s Othello – the classic tragedy of deceit, revenge, love, and jealousy... in essence, all the makings for the spectacle and drama that is opera.

Shakespeare’s Othello – the classic tragedy of deceit, revenge, love, and jealousy... in essence, all the makings for the spectacle and drama that is opera.

Not every great composer has been lucky enough to find a librettist of equal inspiration. Benjamin Britten, however, was blessed with several superb librettists, whose creations not only match the excellence of his music, but stand on their own as works of real literary merit. The libretto for Billy Budd is a prime example. Adapted from Herman Melville's unfinished novella by novelist E.M. Forster and longtime Britten collaborator Eric Crozier, it is at once readily intelligible and powerfully poetic. Britten's extraordinary score could ask for no better partner.

Not every great composer has been lucky enough to find a librettist of equal inspiration. Benjamin Britten, however, was blessed with several superb librettists, whose creations not only match the excellence of his music, but stand on their own as works of real literary merit. The libretto for Billy Budd is a prime example. Adapted from Herman Melville's unfinished novella by novelist E.M. Forster and longtime Britten collaborator Eric Crozier, it is at once readily intelligible and powerfully poetic. Britten's extraordinary score could ask for no better partner.  The opera may be titled Billy Budd, but ultimately it is Captain Vere, and not Billy, who is its centre. Vere's moral crisis is the crux of the story, and it is his tormented recollections which frame the opera, as prologue and epilogue. English tenor Philip Langridge is arguably the finest Britten tenor of his generation and he is stunning in this vital role. Age has brought to his voice an ideal patina of craggy maturity, mingled still with a freshness of tone which makes Langridge equally convincing as both and old man and as his younger self. He doesn't so much play the role as inhabit it completely, giving a performance of rare poignancy - truly a privilege to behold.

The opera may be titled Billy Budd, but ultimately it is Captain Vere, and not Billy, who is its centre. Vere's moral crisis is the crux of the story, and it is his tormented recollections which frame the opera, as prologue and epilogue. English tenor Philip Langridge is arguably the finest Britten tenor of his generation and he is stunning in this vital role. Age has brought to his voice an ideal patina of craggy maturity, mingled still with a freshness of tone which makes Langridge equally convincing as both and old man and as his younger self. He doesn't so much play the role as inhabit it completely, giving a performance of rare poignancy - truly a privilege to behold.

Swords, tartan and leg-of-mutton sleeves abound in John Copley's production of Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor for Opera Australia. At twenty-eight years of age, it's one of the oldest productions still in repertory, but it's also something of a classic. Michael Stennett's opulent period costumes and Henry Bardon's imposing architectural features set the scene for a night of good, old-fashioned bel canto - short on drama, but with plenty of heart and enough beautiful singing to gladden the most jaded heart.

Swords, tartan and leg-of-mutton sleeves abound in John Copley's production of Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor for Opera Australia. At twenty-eight years of age, it's one of the oldest productions still in repertory, but it's also something of a classic. Michael Stennett's opulent period costumes and Henry Bardon's imposing architectural features set the scene for a night of good, old-fashioned bel canto - short on drama, but with plenty of heart and enough beautiful singing to gladden the most jaded heart.  Eric Cutler is a remarkably tender and sweet-toned Edgardo, more lover than fighter, despite his sword-brandishing heroics. His bright and beautiful sound blends wonderfully with Matthews' crystalline Lucia in their Act I duet; his "Tombe degli avi miei" is even more impressive, displaying intelligent phrasing, melting legato and a stunningly controlled upper register. José Carbo is similarly excellent as the other man in Lucia's life, her scheming brother Enrico. Carbo's vivid stage presence brings a dash of individuality to this melodramatic role, making him a cruel but charismatic villain. His rich, muscular baritone is consistently thrilling; the duet with Edgardo in the Wolf's Crag scene is particularly electrifying.

Eric Cutler is a remarkably tender and sweet-toned Edgardo, more lover than fighter, despite his sword-brandishing heroics. His bright and beautiful sound blends wonderfully with Matthews' crystalline Lucia in their Act I duet; his "Tombe degli avi miei" is even more impressive, displaying intelligent phrasing, melting legato and a stunningly controlled upper register. José Carbo is similarly excellent as the other man in Lucia's life, her scheming brother Enrico. Carbo's vivid stage presence brings a dash of individuality to this melodramatic role, making him a cruel but charismatic villain. His rich, muscular baritone is consistently thrilling; the duet with Edgardo in the Wolf's Crag scene is particularly electrifying.

Monteverdi’s The Coronation of Poppea is a tale of ambition and manipulation intertwined with love and passion – the perfect recipe for drama. Poppea is a fiery, determined woman who uses her sexuality to secure the throne. Director Kate Cherry draws parallels between Poppea and Paris Hilton - Monteverdi seems to have captured the timeless essence of excess mixed with passion and desire for power.

Monteverdi’s The Coronation of Poppea is a tale of ambition and manipulation intertwined with love and passion – the perfect recipe for drama. Poppea is a fiery, determined woman who uses her sexuality to secure the throne. Director Kate Cherry draws parallels between Poppea and Paris Hilton - Monteverdi seems to have captured the timeless essence of excess mixed with passion and desire for power.

Verdi's Otello is a rare bird. Arguably the composer's finest dramatic opera, it is also one of very few Shakespearean operas to do justice to the Bard. That's thanks partly to a composer as prodigiously gifted in his own field as Shakespeare was in his, and partly to Arrigo Boito's superbly concise adaptation, which removes much of the play's action and several of its characters while losing none of its impact. Stripped to bare essentials, Boito's libretto is a concentrated examination of the precarious personal relationships which are at the play's core. The score is one of Verdi's most extraordinary, his orchestral writing mingling clashing violence with swirling lyricism. Vocal lines are mostly fluid and naturalistic, eschewing the traditional recitative/aria structure, but incorporating several stunning set pieces.

Verdi's Otello is a rare bird. Arguably the composer's finest dramatic opera, it is also one of very few Shakespearean operas to do justice to the Bard. That's thanks partly to a composer as prodigiously gifted in his own field as Shakespeare was in his, and partly to Arrigo Boito's superbly concise adaptation, which removes much of the play's action and several of its characters while losing none of its impact. Stripped to bare essentials, Boito's libretto is a concentrated examination of the precarious personal relationships which are at the play's core. The score is one of Verdi's most extraordinary, his orchestral writing mingling clashing violence with swirling lyricism. Vocal lines are mostly fluid and naturalistic, eschewing the traditional recitative/aria structure, but incorporating several stunning set pieces.  Best of all is Jonathan Summers' diabolical Iago, a figure of inhuman - yet shockingly believable - evil and cruelty. Iago's presence is made all the more unsettling by his army uniform and jackboots; his "Credo in un dio crudel" is delivered with horrifying sincerity and shades of Nuremberg. Summers' slightly threadbare baritone is ideally suited to his purpose, and he manipulates it brilliantly - snarling one moment, smoothly persuasive the next.

Best of all is Jonathan Summers' diabolical Iago, a figure of inhuman - yet shockingly believable - evil and cruelty. Iago's presence is made all the more unsettling by his army uniform and jackboots; his "Credo in un dio crudel" is delivered with horrifying sincerity and shades of Nuremberg. Summers' slightly threadbare baritone is ideally suited to his purpose, and he manipulates it brilliantly - snarling one moment, smoothly persuasive the next.  Don Giovanni is Mozart's darkest, most ambiguous work. Comic episodes punctuate a sinister tale of dark deeds and darker consequences; stock opera buffa characters mingle with - and themselves become - villains and victims. Such fascinating complexity invites subversive interpretation, and numerous directors have proved powerless to resist. Most recent to heed that call is Australia's Elke Neidhardt, whose bleak, black 21st century Don Giovanni opened this week in Sydney.

Don Giovanni is Mozart's darkest, most ambiguous work. Comic episodes punctuate a sinister tale of dark deeds and darker consequences; stock opera buffa characters mingle with - and themselves become - villains and victims. Such fascinating complexity invites subversive interpretation, and numerous directors have proved powerless to resist. Most recent to heed that call is Australia's Elke Neidhardt, whose bleak, black 21st century Don Giovanni opened this week in Sydney.  Hungarian bass Gabor Bretz brings rugged self-assurance and a warmly expansive voice to the title role. In manner and in voice, his is a brutish Giovanni, in keeping with Neidhardt's vision; Bretz slides convincingly into character as a present-day bad boy. Narcissism is key - he is most compelling in the manic "Finch'han del vino" and later, in his wretched final scene; moments of suave seduction are less persuasive. Bretz's limelight is very nearly stolen, however, by Joshua Bloom's terrific Leporello. Bloom is the ideal comic foil, providing humour without resorting to pantomime comedy; he's also in magnificent voice, his "Madamina, il catalogo è questo" as mellifluous as it is funny.

Hungarian bass Gabor Bretz brings rugged self-assurance and a warmly expansive voice to the title role. In manner and in voice, his is a brutish Giovanni, in keeping with Neidhardt's vision; Bretz slides convincingly into character as a present-day bad boy. Narcissism is key - he is most compelling in the manic "Finch'han del vino" and later, in his wretched final scene; moments of suave seduction are less persuasive. Bretz's limelight is very nearly stolen, however, by Joshua Bloom's terrific Leporello. Bloom is the ideal comic foil, providing humour without resorting to pantomime comedy; he's also in magnificent voice, his "Madamina, il catalogo è questo" as mellifluous as it is funny.

Arabella, the eponymous heroine of Richard Strauss’s comic opera is looking for love. She is a poor little rich girl seeking a ‘master’ to whom she will be ‘as obedient as a child’ and a firm believer in the notion of ‘Mr. Right’. Her parents alas have other plans for her, namely that she be sold to the highest bidder in order to rescue the families floundering fortunes by means of a profitable marriage. Count Waldner, Arabella’s gambling father who is responsible for their financial demise, sends a picture of Arabella to a decrepit old army friend in the hope of snaring a wealthy husband for his maiden daughter. Fortunately for our heroine the old goat has long gone and the picture ends up in the hands of his wealthy young nephew Mandryka. This ‘prince charming’ character, having been attacked by an over enthusiastic bear and unable to get out of bed for three months, spends the entire time dreaming about the girl in the picture before heading off to Vienna to claim her as his bride.

Arabella, the eponymous heroine of Richard Strauss’s comic opera is looking for love. She is a poor little rich girl seeking a ‘master’ to whom she will be ‘as obedient as a child’ and a firm believer in the notion of ‘Mr. Right’. Her parents alas have other plans for her, namely that she be sold to the highest bidder in order to rescue the families floundering fortunes by means of a profitable marriage. Count Waldner, Arabella’s gambling father who is responsible for their financial demise, sends a picture of Arabella to a decrepit old army friend in the hope of snaring a wealthy husband for his maiden daughter. Fortunately for our heroine the old goat has long gone and the picture ends up in the hands of his wealthy young nephew Mandryka. This ‘prince charming’ character, having been attacked by an over enthusiastic bear and unable to get out of bed for three months, spends the entire time dreaming about the girl in the picture before heading off to Vienna to claim her as his bride. Arabella is the beloved daughter of the Waldners, an aristocratic family of rapidly diminishing means. Their survival depends on a good marriage for their daughter; Arabella has no shortage of suitors but steadfastly awaits "the right man". She finds him in Mandryka. But the Waldners have another daughter, Zdenka, who has been raised as a boy - bringing two daughters out in 19th century Viennese society would be far too expensive. Zdenka unrequitedly loves Arabella's most ardent admirer, Matteo, and forges letters to him from her sister which she passes on in her guise as "Zdenko", Arabella's sister and Matteo's confidant.

Arabella is the beloved daughter of the Waldners, an aristocratic family of rapidly diminishing means. Their survival depends on a good marriage for their daughter; Arabella has no shortage of suitors but steadfastly awaits "the right man". She finds him in Mandryka. But the Waldners have another daughter, Zdenka, who has been raised as a boy - bringing two daughters out in 19th century Viennese society would be far too expensive. Zdenka unrequitedly loves Arabella's most ardent admirer, Matteo, and forges letters to him from her sister which she passes on in her guise as "Zdenko", Arabella's sister and Matteo's confidant.  Singing Mandryka is Barker's real-life partner, baritone Peter Coleman-Wright. Unsurprisingly, the chemistry between the two is potent. When, in the duet "Und du wirst mein Gebieter sein", they pledge themselves to one another, the electricity is palpable. Indeed, it's hard to know whether to watch, amazed, or turn aside and give them their privacy. Coleman-Wright's Mandryka is a genial and appealing creation; what his voice lacks in outright splendour he makes up for in elegant phrasing and smooth, Straussian legato.

Singing Mandryka is Barker's real-life partner, baritone Peter Coleman-Wright. Unsurprisingly, the chemistry between the two is potent. When, in the duet "Und du wirst mein Gebieter sein", they pledge themselves to one another, the electricity is palpable. Indeed, it's hard to know whether to watch, amazed, or turn aside and give them their privacy. Coleman-Wright's Mandryka is a genial and appealing creation; what his voice lacks in outright splendour he makes up for in elegant phrasing and smooth, Straussian legato.  Giuseppe Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera (A Masked Ball) is considered by some to be a masterpiece whilst others have described it as his ‘worst opera’; and whilst Opera Australia’s current production is not the ‘worst opera’ I have seen, it is disappointing. Wednesday’s opening night performance is a good example of all the worst stereotypes that people think of when the word ‘opera’ is mentioned; these include overacting, ridiculous costumes, and portly singers bellowing in unattractive tones about an impossible and unrequited love.

Giuseppe Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera (A Masked Ball) is considered by some to be a masterpiece whilst others have described it as his ‘worst opera’; and whilst Opera Australia’s current production is not the ‘worst opera’ I have seen, it is disappointing. Wednesday’s opening night performance is a good example of all the worst stereotypes that people think of when the word ‘opera’ is mentioned; these include overacting, ridiculous costumes, and portly singers bellowing in unattractive tones about an impossible and unrequited love.