Murray Black | September 26, 2008

Billy Budd by Benjamin Britten. Opera Australia. Conductor: Richard Hickox. Director: Neil Armfield. Sydney Opera House, September24. Tickets: $99-$240. Bookings: (02) 9318 8200. Until October 16.

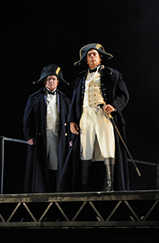

TEN years after its premiere, director Neil Armfield's production of Benjamin Britten's opera Billy Budd remains fresh and compelling. Dominated by a movable rectangular platform that rises, falls and circles an otherwise sparse stage, its great virtue is that nothing is allowed to distract from the moral drama that unfolds.

At this production's core are three magnificent performances. Although Peter Coleman-Wright's singing in the original production had greater richness of tone and complexity of colour, fellow baritone Teddy Tahu Rhodes is still a fine Billy Budd. Singing with a clear, focused tone and impressive agility, his firm, youthful-sounding voice is well suited to his character's exuberant good nature. Rhodes's characterisation is a winning mix of virile magnetism, artless simplicity and, ultimately, moral strength. And, yes, his shirt does come off for a while during the first act.

Tenor Philip Langridge's Aschenbach in Opera Australia's 2005 production of Britten's Death in Venice was extraordinary. Here, as Captain Vere, he is almost as good. Despite showing occasional signs of strain in his top register, Langridge's sinuous line, superb diction and sensitive phrasing illuminate Vere's inner torment at the excruciating moral dilemma he faces. He wants to save Billy from the gallows but his sense of duty cannot allow it. The pain and grief at what he is forced to do are seared into Langridge's vocal timbre.

As the black-hearted Claggart, bass-baritone John Wegner almost steals the show. It is a commanding performance of imposing malevolence and slow-burning intensity. He sings with stamina and strength, investing his voice with a burnished dark-hued tone. Wegner also captures his character's seething heart of darkness. Homoerotism is acknowledged without being overdone and twisted self-loathing adds complexity to a convincing portrait of evil.

The three leads receive able support from the rest of the all-male cast. The male chorus also has a prominent role in this opera. Sustaining good balance and blend throughout, they're equally impressive in hushed, sotto voce passages and full-voiced, fortissimo outbursts.

Apart from the occasional blemish, the orchestra responds to Richard Hickox's inspired direction with polish and refinement.

OA has been criticised recently for its musical standards and production qualities. There can be no more eloquent rebuttal than this outstanding production.

Not every great composer has been lucky enough to find a librettist of equal inspiration. Benjamin Britten, however, was blessed with several superb librettists, whose creations not only match the excellence of his music, but stand on their own as works of real literary merit. The libretto for Billy Budd is a prime example. Adapted from Herman Melville's unfinished novella by novelist E.M. Forster and longtime Britten collaborator Eric Crozier, it is at once readily intelligible and powerfully poetic. Britten's extraordinary score could ask for no better partner.

Not every great composer has been lucky enough to find a librettist of equal inspiration. Benjamin Britten, however, was blessed with several superb librettists, whose creations not only match the excellence of his music, but stand on their own as works of real literary merit. The libretto for Billy Budd is a prime example. Adapted from Herman Melville's unfinished novella by novelist E.M. Forster and longtime Britten collaborator Eric Crozier, it is at once readily intelligible and powerfully poetic. Britten's extraordinary score could ask for no better partner.  The opera may be titled Billy Budd, but ultimately it is Captain Vere, and not Billy, who is its centre. Vere's moral crisis is the crux of the story, and it is his tormented recollections which frame the opera, as prologue and epilogue. English tenor Philip Langridge is arguably the finest Britten tenor of his generation and he is stunning in this vital role. Age has brought to his voice an ideal patina of craggy maturity, mingled still with a freshness of tone which makes Langridge equally convincing as both and old man and as his younger self. He doesn't so much play the role as inhabit it completely, giving a performance of rare poignancy - truly a privilege to behold.

The opera may be titled Billy Budd, but ultimately it is Captain Vere, and not Billy, who is its centre. Vere's moral crisis is the crux of the story, and it is his tormented recollections which frame the opera, as prologue and epilogue. English tenor Philip Langridge is arguably the finest Britten tenor of his generation and he is stunning in this vital role. Age has brought to his voice an ideal patina of craggy maturity, mingled still with a freshness of tone which makes Langridge equally convincing as both and old man and as his younger self. He doesn't so much play the role as inhabit it completely, giving a performance of rare poignancy - truly a privilege to behold.